Solving Websocket Communication

Websockets are a great tool for fast 2-way communication. However, they have some caveats when dealing with devices on a local network.

This post was originally published on touchdeck.app.

The First Steps

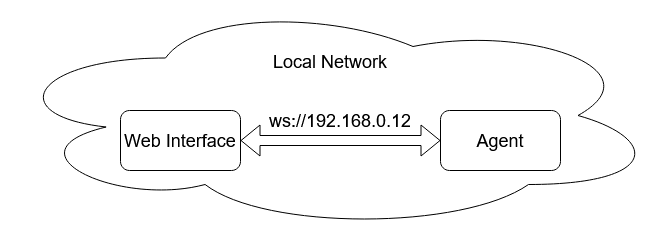

Initially the TouchDeck was built to communicate only over the local network. This meant that the web interface made a direct websocket connection to the agent. This was the simplest way to start developing the TouchDeck, and seemed to be good enough.

Deploying the Deck

To really start using the deck I had to deploy it to a domain rather than serving the web interface from my development machine every time. I picked and set up the touchdeck.app domain, but after running a test deployment I encountered some issues that completely prevented me from being able to use the deck.

Enter HSTS Preloading

As it turns out, all .app domains have HSTS preloading enabled by default. HSTS preloading is a technology that enforces secure HTTPS connections from the browser to a website, even before the first connection is made. The HSTS registry is essentially a list of domain names that is hardcoded into browsers, which are only allowed to use HTTPS. To learn more about HSTS preloading, check hstspreload.org.

Besides HSTS preloading, there are other reasons to use HTTPS instead of plain HTTP. Viewing a website over HTTP will (in most modern browsers) show a “Not secure” warning next to the URL. While this may not directly be a problem, it can (and likely will) scare away users.

HTTPS and Websockets

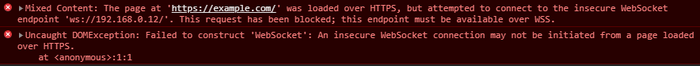

So plain HTTP was out of the question, and the deck would be served over HTTPS. This also means that we can’t load plain HTTP resources, since browsers don’t allow you to downgrade the security. Since a websocket connection starts with an HTTP request, this means we also have to use secure websockets (WSS instead of plain WS). Trying to construct a plain websocket on a page served over HTTPS will give an error, similar to this:

Rethinking the Connection

Given all this information, our initial strategy of connecting directly from the web interface to the agent over the local network is out of the question. To create a secure websocket connection we need a certificate, and to get a certificate we need a domain name. This means there is no way to create a secure WSS connection to a local IP address.

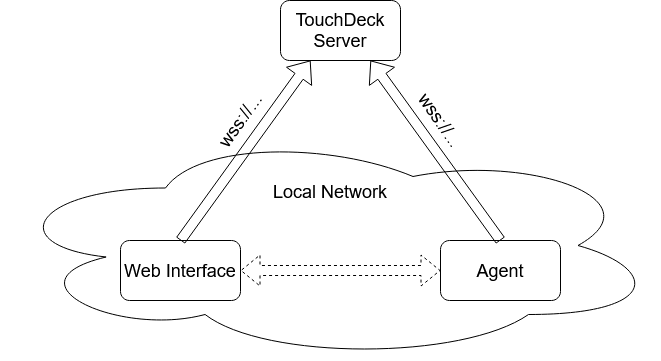

After some experimentation (and drawing various diagrams) I figured that the best way to handle connections between the web interface and agent, would be to proxy them via the TouchDeck server. This meant creating a websocket proxy that both the web interface and the agent can connect to. Ideally this would only change the way the connections were made, and after that all websocket communication would remain the same.

This led to the creation of the websocket-proxy project, a simple websocket proxy server written in Go capable of proxying messages between web interfaces and agents. It also acts as a local discovery server, as it allows the web interface to list the agents which are running on the same local network. However, unlike the first architecture iteration, it’s not limited to web interfaces and agents that are running on the same local network.

And with that, the websocket communication problem is solved… for now.

Limitations and Possible Improvements

In order to speed up development for the initial version, and to test how well the websocket proxy would work in practice, it was designed to be a single-instance server. This means it’s not possible to scale it by running multiple instances on different servers. While this will likely be fine for lower traffic, this may (or rather, will hopefully) become an issue as more people start to use TouchDeck. This could be improved by using a message broker (such as RabbitMQ) to distribute websocket messages between multiple instances of the proxy, but that’s a topic for a later blog post.